![]()

Rameses II 1279 – 1213 BC

Usr-Maat-Ra Setep-en-Ra Ra-messu-Meri-Amun

Rameses II (right 19th dynasty), son of Seti I, was around thirty years old when he became king of Egypt – and then reigned for 67 years. He had many wives, among them some of his own near relatives, and was the father of about 111 sons and 51 daughters.

As was usual in those days, the threat of foreign aggression against Egypt was always at its greatest on the ascension of a new Pharaoh. Subject kings no doubt saw it as their duty to test the resolve of a new king in Egypt. Likewise, it was incumbent on the new Pharaoh it make a display of force if he was to keep the peace during his reign. Therefore, in his fourth year as pharaoh, Rameses was fighting in Syria in a series of campaigns against the Hittites and their allies. The Hittites, however, were a very strong foe and the war lasted for twenty years.

On the second campaign, Rameses found himself in some difficulties when attacking “the deceitful city of Kadesh”. This action nearly cost him his life. He had divided his army into four sections: the Amun, Ra, Ptah and Setekh divisions. Rameses himself was in the van, leading the Amon division with the Ra division about a mile and a half behind. He had decided to camp outside the city – but unknown to him, the Hittite army was hidden and waiting. They attacked and routed the Ra division as it was crossing a ford. Rameses II from the Ramesseum – his mortuary temple on the West bank at LuxorWith the chariots of the Hittites in pursuit, Ra fled in disorder – spreading panic as they went. They ran straight into the unsuspecting Amun division. With half his army in flight, Rameses found himself alone. With only his bodyguard to assist him, he was surrounded by two thousand five hundred Hittite chariots.

The king, realising his desperate position, charged the enemy with his small band of men. He cut his way through, slaying large numbers as he escaped. “I was,” said Rameses, “by myself, for my soldiers and my horsemen had forsaken me, and not one of them was bold enough to come to my aid.”

At this point, the Hittites stopped to plunder the Egyptian camp – giving the Egyptians time to regroup with their other two divisions. They then fought for four hours, at the end of which time both sides were exhausted and Rameses was able to withdraw his troops.

In the end neither side was victorious. And finally – after many years of war – Rameses was obliged to make a treaty with the prince of the Hittites. It was agreed that Egypt was not to invade Hittite territory, and likewise the Hittites were not to invade Egyptian territory. They also agreed on a defence alliance to deter common enemies, mutual help in suppressing rebellions in Syria, and an extradition treaty.

Thirteen years after the conclusion of this treaty in the thirty-fourth year of his reign, Rameses married the daughter of the Hittite prince. Her Egyptian name was Ueret-ma-a-neferu-Ra: meaning ” Great One who sees the Beauties of Ra”.

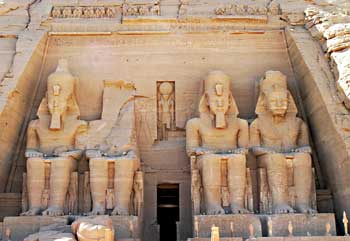

Although brave in battle, Rameses was an inept general – and I wonder how Thutmose III would have dealt with the Hittites. Maybe Rameses also pondered this because he spent the rest of his life bolstering his image with huge building projects. His name is found everywhere on monuments and buildings in Egypt and he frequently usurped the works of his predecessors and inscribed his own name on statues which do not represent him. The smallest repair of a sanctuary was sufficient excuse for him to have his name inscribed on every prominent part of the building. His greatest works were the rock-hewn temple of Abu Simbel, dedicated to Amun, Ra-Harmachis, and Ptah; its length is 185 feet, its height 90 feet, and the four colossal statues of the king in front of it – cut from the living rock – are 60 feet high. He also added to the temple of Amenhotep III at Luxor and completed the hall of columns at Karnak – still the largest columned room of any building in the world.

Although he is probably the most famous king in Egyptian history, his actual deeds and achievements cannot be compared with the great kings of the 18th dynasty. He is, in my opinion, unworthy of the title ‘Great’. A show-off and propagandist, he made his mark by having his name, like a graffiti artist, inscribed on every possible stone. Whereas kings such as Thutmose III left a stronger and more dynamic Egypt, after Rameses death Egypt fell into decline. Luckily for Egypt, her prestige and pre-eminence as a world superpower was such that this process took a long time. Only one other king, Rameses III (1184 – 1153 BC), was able to temporarily halt this process.

Ancient Egyptian Anecdotes

The Ancient Egyptians in their own words

Illustrated Papyri translations edited for the modern reader.